The Royal National Hospital for Chest Diseases

A Victorian Hospital

The Royal National Hospital for Chest Diseases, located at Steephill on the Undercliff, near the town of Ventnor on the Isle of Wight was founded to treat diseases of the chest, specifically Consumption or as it became and better known Tuberculosis –TB.

The Royal National Hospital was founded by Arthur Hill Hassall, ‘polymath’ Victorian doctor of medicine, biological sciences and pioneer of public health regulations and legislation. He chose the site at Ventnor, Isle of Wight principally for the quality of its natural environment, whose contribution to his own recovery from the disease in 1866 he regarded as instrumental. As a consequence this led him to decide to found and build the hospital at Ventnor and to advocate, celebrate and make the heath promoting properties of its climate and environment available to all. The Hospital lasted for 96 years from 1868 – 1964.

Consumption or Phthisis as it was then called was widespread in C18th and C19th Britain – in 1815 one in four deaths was caused by the disease and 50% of those who acquired the disease, if untreated, went on to die. The disease typically attacks the lungs spreading to other parts of the body. Symptoms are a chronic cough with blood-tinged sputum, fever, night sweats and weight loss. There was no effective treatment. Medicines, largely based on long standing herbal and homeopathic remedies, expanded considerably by the discovery of plant species outside Europe from C16th, combined with studies and experiments into the chemistry of minerals, only alleviated the symptoms and did not provide any effective longer lasting cure.

Rather the prevailing view of the C19th medical profession, of whom Arthur Hill Hassall was a pre-eminent member, was that the character and qualities of the environment in which healthcare and treatment of illness were delivered were critical to the successful management of the progress and possible cure of illness. This was combined with the expanding understanding of nutritional science and the knowledge obtained through microbiology. However it was not until the end of the century that the actual bacteria that caused TB was isolated and indeed recognised and understood that TB was in fact an infectious illness passed from person to person. Arthur Hill Hassall as a microbiologist must have understood this possibility which led him to establish treatment at Ventor on the ‘separate principle’ of single rooms.

Only in 1946 was the first effective cure and treatment for TB found with the development of the antibiotic ‘streptomycin’ and the safe introduction of the vaccine BCG. Eventually control of the disease in Britain led rapidly to a specialist National or a local Hospital no longer being required and in 1964 treatment of ‘pulmonary’ illnesses on the Isle of Wight was absorbed into the ‘infectious disease' wards at St. Mary’s Hospital, Newport as was the case with local hospitals across the country. As a consequence the Royal National Hospital closed and within 4 years was demolished – its original objectives and ideals disappearing from everyday consciousness and almost forgotten. However today in 2015, throughout the World, the tuberculosis bacteria still remains highly infectious with an estimated one third of the World’s existing population having experienced the disease and 1% of the World’s population becoming newly infected each year.

The C19th saw a huge expansion of hospital and healthcare provision in Britain arising from rapid changes in society and the ways in which persons thought about and viewed the world. In the later part of C18th and early C19th ‘Romanticism’ had come to be the dominant philosophical and intellectual set of ideas and artistic movement in Europe, rebelling against the established hierarchical rules, theory and conventions around ‘Neo Classicalism’. Romanticism developed a new concept of thought around the primacy of the ‘individual’ and released a new energy encouraging persons to break through boundaries into new fields of enquiry and achievement in both the arts and natural sciences.

The impetus for ‘Romanticism’ gained political momentum with the French Revolution in 1789 leading to the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and a century of ‘revolutions’ across Europe. In Britain ‘Romanticism’ became central to its culture with the poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge publishing their ‘Lyrical Ballads’ in 1798 and transforming literature and the way culture influenced society for the remainder of the C19th. In the visual arts Francisco Goya in Spain used the Imagination as the power behind his imagery and J.M.W Turner in Britain used the depiction of natural forces, grand landscapes and the ‘sublime’ as the primary motif in both his panoramic canvases and watercolours. Between 1770-79 James Cook discovered Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Ocean. As a consequence scientists commenced a worldwide exploration into and expansion of the natural sciences amongst which were the journeys of Charles Darwin leading to the publication of his ‘Origin of the Species’ in 1859.

When access to the continent of Europe was restricted by the French Revolution in 1789 and then the Napoleonic Wars 1799-1815, artists and writers in Britain started to explore the British coastline to replace the ‘Grand Tour’. J.M.W Turner visited the Isle of Wight on several occasions in the 1790s as did other artists from the Royal Academy - Charles Tomkins, Thomas Rowlandson and George Morland – developing an ‘Isle of Wight School’ of painting based on its landscape, coastal and marine subjects. This popularisation and ‘romanticisation’ of the Island landscape and coastline led to a great interest by wealthier persons in the recreational, therapeutic and health promoting properties of the coast outside urban conurbations, especially those of London, Manchester and those towns referred to by William Blake as ‘..dark satanic mills.. / Jerusalem 1804’, where sanitation was poor, housing overcrowded and the incidence of disease high.

One of these persons was John Keats, who had originally qualified as an apothecary and surgeon in 1816 but decided his true vocation was as a Poet. In 1818 he contracted ‘consumption’ – TB, probably from nursing his brother who died of the disease in London. In 1817 and 1818 he visited the Isle of Wight – Carisbrooke and Shanklin, and was inspired by the landscape, coastline and particularly the ‘wondrous Chine’.

Reflecting on his experience it was here in 1818 that he wrote and then

published his poem ‘Endymion’:

‘Endymion’

“A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Therefore, on every morrow, are we wreathing

A flowery band to bind us to the earth,

Spite of despondence, of the inhuman dearth

Of noble natures, of the gloomy days,

Of all the unhealthy and o’er-darkened ways

Made for our searching: yes, in spite of all,

Some shape of beauty moves away the pall

From our dark spirits. Such the sun, the moon,

Trees old and young, sprouting a shady boon

For simple sheep; and such are daffodils

With the green world they live in; and clear rills

That for themselves a cooling covert make

‘Gainst the hot season; the mid forest brake,

Rich with a sprinkling of fair musk-rose blooms:

And such too is the grandeur of the dooms

We have imagined for the mighty dead;

All lovely tales that we heard or read:

An endless fountain of immortal drink,

Pouring unto us from the heaven’s brink.”

The Isle of Wight came to be transformed in the C19th. From a small rural population of just a few thousand, whose previous importance was only as a line of defence against foreign invasion, and a coast feared for shipwrecking and notorious for smuggling the Island became to be the most fashionable place for Victorian Society to live, for vacations, to see and be seen and to experience the health promoting properties of its coastal climate. In 1814 the Pier at Ryde was built, acting as a gateway to the Isle of Wight, enabling steam boats to bring a huge influx of visitors and new residents to the Island who transformed its economy and identity. The character and reputation of the Undercliff from Shanklin to Niton spread rapidly. The Undercliff geologically is an ancient six mile long narrow coastal landslide below the chalk Downs, having a sheltered south facing location, a warm micro-climate, lush vegetation and important habitats for many plant, insect, bird and animal species. In 1820 Sir James Clark, who was later in 1837 to become ‘Physician-in-Ordinary’ to Queen Victoria, treated John Keats for his consumption. He was particularly of the view that the climate and mineral waters were the most effective treatment in the recovery from consumption and in 1829 published ‘The Influence of Climate in the Preparation and Cure of Chronic Disease, more particularly of the Chest and Digestive Organs’ and drew attention in particular to the south coast of the Isle of Wight as a suitable destination.

Prior to 1830 the population of Ventnor was seventy-seven. There then followed a period of feverish speculative development as the perceived beneficial qualities of its climate made it one of the most fashionable and desirable place to live or visit in Britain. The 200 acre Littleton farm and 130 acre Ventnor farm were sold piecemeal for building with land values rising from £100 to £800 an acre. In the early 1860s Ventnor constructed its own harbour and pier with ferry connections direct to the mainland, France and the Continent and then in 1866 the railway direct to Ventnor opened. By 1851 the population had risen to 3,000 and by the end of the century to almost 6,000. The Isle of Wight during the C19th enjoyed a status at the centre of British and European Society. In 1798 the architect John Nash designed and built East Cowes Castle as his principal home. In 1835 John Hambrough had Steephill Castle built for him on the Undercliff – on the north side of the road opposite to where the Royal National Hospital was to be built in 1868. In 1845 Thomas Cubitt built Osborne House at East Cowes for Queen Victoria to the design of her husband Prince Albert.

Writers and artists, both British and International, continued to find inspiration from the Island’s character. Charles Dickens visited in 1849, stayed at adjacent Bonchurch and wrote ‘David Copperfield’. In 1867 Charles Darwin stayed for the summer at the ‘King’s Head’ Hotel in Sandown working on his ‘Origin of Species: an assessment’ whilst in 1868 the American poet Henry Longfellow stayed at Shanklin. In 1875 Lewis Carroll whilst in Sandown wrote his poem ‘The Hunting of the Snark’. Also in 1875 the French Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, married to Eugene Manet, the brother of the painter Edouard Manet, came to the Isle of Wight and established her studio on the Island over two consecutive summers. Karl Marx, who had developed TB, visited Ryde regularly during the 1870’s, then Ventnor in 1880, 1882 and 1883 the final years of his life staying at St Boniface Gardens. From 1880 Algernon Swinburne the poet built and made his permanent home at East Dene in Bonchurch moving from Cheyne Walk, Chelsea to recover his health and remained there for the rest of his life.

In 1874 the inhabitants of Ventnor experienced an event comparable to that of a contemporary Pop Festival or visit by a C21st celebrity. The Empress of Austria and her sister the ex-Queen of Naples descended upon and came to live at Ventnor for two consecutive years renting Steephill Castle adjacent to the Royal National Hospital, upgrading it with bathrooms, kitchens and stables whilst the Crown Princess of Germany vacationed nearby in Sandown. Attracted by the climate, sea-bathing and the social scene, between them they had a huge entourage of ladies- in-waiting, chaplains, governesses, doctors, nurses, hairdressers, French and Hungarian chefs, maids and grooms, horses and hounds. The Empress chose Ventnor apparently as she found the Court at Osborne too formal and stuffy. Ventnor and the Undercliff gave her free rein. She personally accepted the Invitation from the Board of Governors to open the second phase of the building of the Royal National Hospital adjacent to Steephill Castle in 1875.

The range of celebrated visitors continued well into the C20th. Winston Churchill spent boyhood summers from 1888 in Bonchurch and Ventnor. In 1889 Edward Elgar the composer and his wife spent their honeymoon on the Eastern Cliffs at Alexandra Gardens, Ventnor. In 1890 Mahatma Ghandhi and his family spent the summer at Sheltons vegetarian Hotel, Madeira Road, where nearby earlier in 1850 Lord Macaulay had written part of his ‘History of England’. In 1929 the poet Alfred Noyes moved to Lislecombe on the Undercliff, adjacent on the western boundary to the Royal National Hospital where he lived until 1958 and in 1938 the Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethopia holidayed in Ventnor on the Esplanade and visited Henry de Vere Stacpoole, the writer of 90+ novels who had made his home in Bonchurch. After 1950, with the increasing ability of persons to fly around the world on cheap(er) holidays without the British climate, Ventnor and the Undercliff became largely ‘the town the world forgot’ – except as a curious listing at the base of newspaper weather reports, slowly disappearing from the public consciousness. The Royal National Hospital closed in 1964. Several attempts, all in vain, were made to find a buyer or discover a new use – a public planning enquiry in 1967 ruled out the site becoming a holiday camp or development for housing and with C19th Victorian architecture being deeply out of fashion no ‘heritage listing’ of the building was there to preserve it. Steephill Castle across the road had been demolished in 1963 as had also previously East Cowes Castle in 1960 after both falling into disrepair and neglect. So it was agreed that the best option was to demolish the Royal National Hospital building in its entirety and turn the site, and by now its overgrown surrounding gardens, into a Botanical Garden modelling the example of Kew Gardens in London with the support of the Hampshire plants man Harold Hillier.

Ventnor and the Undercliff and the Botanic Gardens became a ‘best kept secret’ gradually attracting new residents such as Michael Harris who founded the ’Isle of Wight Glass’ hot glassworks at St. Lawrence in 1973. The geologist and world authority on coastal land management Robin McInnes, who lives in St.Lawrence, founded and managed the ‘Isle of Wight Centre for the Coastal Environment’ in Ventnor from 1995-2007. Ventnor Botanic Gardens is now one of the pre-eminent Botanic Gardens in the UK with its unique microclimate and a distinctive approach to the promotion and growing of plant species from across continents pioneered by its former curator Simon Goodenough and now led by its current curator Chris Kidd. No longer owned or managed by the Isle of Wight Council it is being managed by its own ‘Community Interest Company’.

At the turn of the C21st the 2009 Census records the population of Ventnor as 6,180 with over 30% of persons aged over 65 and with a life expectancy of 81 years (43 yrs in 1850, 50 yrs in 1900, and 65 yrs in 1950). The average number of persons now contracting TB on the Isle of Wight each year between 2011 – 2013 is recorded as just 4.7 compared to the C19th when it was recorded that for 25% of the population TB was listed as their cause of death.

In 1866 into this elegiac Elysian environment, febrile and fashionable society, arrived Arthur Hill Hassall. Born in 1817 Arthur Hill Hassall was a Victorian ‘polymath’, being a highly qualified and experienced physician, microscopist and naturalist. His apprenticeship was spent in the hospitals of Dublin where he gained a diploma in midwifery in 1837 from Trinity College becoming a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1839, awarded the diploma of the Society of Apothecaries in 1841, qualifying as a Doctor in 1842, in 1851 becoming a member of the Royal College of Physicians and a Fellow of the Linnaean Society. In 1845 he published his book ‘History of the British Freshwater Algae’, and in 1849 ‘The Microscopic Anatomy of the Human Body in Health and Disease’ the first text book on histology – the study of the microscopic structure of animal and plant tissue, with corpuscles found in the spleen being named after him as ‘Hassall’s Corpuscles’. Hassall came to public attention through his microscopical examination in 1850 of the water supply by each of the different Water Companies to London and for his damning and coruscating commentary on its suitability for drinking and other uses highlighting the living organisms in the water as a result of the presence of rotting carcases of animals, flies and maggots. Over this same period he also studied and exposed the wilful and deliberate ‘cover up’ by food manufacturers of the regular adulteration of food with non-original substances, in particular those added to bread, tea and coffee. He published his reports in the Lancet in a succession of articles 1851-1854. In 1855 this led to a Parliamentary Select Committee Enquiry, with Hassall as chief scientific witness, and the first Acts of Parliament– ‘Adulteration Act 1860’ promoting enforceable standards for public health. He established a reputation as Britain’s leading food analyst and became the analytical microscopist for the General Board of Health.

In 1866 Arthur Hill Hassall, having suffered from pleurisy earlier in his life, an inflammation of the lungs, now fell ill with severe lung problems and expectorating - coughing up blood. After long periods in bed he went first to Richmond then to Hastings and St Leonards to recuperate. With no improvement he travelled on to the Isle of Wight and Ventnor where he made a full recovery attributing this to the sunny, sheltered and restful climate. He set up home at St. Catherine’s House in Ventnor building a laboratory to continue his investigation of food adulteration. In 1867 he decided and resolved that it was to be here on the Undercliff, as the best location in Britain, that he would found and build the National Hospital for Chest Diseases a task which he then set out to accomplish over the next 10 years.

The medical profession at this time had not isolated the cause of Phthisis or Consumption – this had to wait until 1882 when Robert Koch isolated the ‘Mycobacterium tuberculosis ‘in Berlin, as well as the causes of cholera and anthrax, together for which he received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1905. However Arthur Hill Hassall with his experience as a microscopist and physician was certainly knowledgeable about the pattern of the disease and convinced of its infectious nature and characteristics. At this time there was no actual cure to be administered. However if certain principles and conditions could be met and provided for Arthur Hill Hassall considered a new Hospital could contribute substantially to a national response to the treatment of the disease with it possible for persons to make a full recovery from the illness.

He stipulated that the Hospital should be in a climate and surroundings that were temperate, with abundant fresh air, sunlight and quiet and where persons, especially those in the early stages of the disease could have and experience complete rest to recuperate, receive an adequate nutritious diet to slowly build their weight and with gentle exercise build their strength and stamina – known as the ‘sanatorium regime’. Patients were also to receive and be administered to with a range of medicinal treatments responsive to the symptoms of the disease and dispensed by an experienced team of physicians, pharmacists and nurses. He specified this treatment on the ‘separate principle’ of patients accommodated in separate individual heated bedrooms with access to a south facing veranda, and as recovery progressed to a shared sitting room for 3-4 persons also with a veranda and then further direct access on to outdoor gardens for exercise. The ‘separate principle ' was advocated specifically to prevent the spread or cross-infection of the disease. Patients received this treatment continuously over a period of weeks amounting to an average stay of 3 to 4 months upon which they would be discharged and return to the home from where they had come – and expressly discouraged to continue to reside in the locality.

The Royal National Hospital for Diseases of the Chest was the first in the UK to be designed on ‘the separate principle’ of treating patients in single rooms to limit cross-infection. It was in complete contrast to the new and prevailing model of the communal ward design of ‘Nightingale’ wards that had been pioneered a few years earlier as a result of the Crimean war and which was to subsequently dominate UK hospital design for the next 150 years. In 1855 the War Office had commissioned Isambard Kingdom Brunel to design a prefabricated Hospital design in timber, which he did in 6 days, and which was then shipped out from Bristol and erected at Renkioi Hospital, Crimea. It was based on a ward unit for 50 persons and focused on improved hygiene and sanitation combined with Florence Nightingale’s new instructions for nursing reportedly reducing the death rate of injured combatants from 42% to 2%. The hospital at Renkioi went on to build further wards to house 1000 persons. The design of Ventnor Hospital in contrast was a very different model based on isolation and supervised exposure to the benign effects of a natural environment which promoted complete rest and quiet. The Royal National Hospital at Ventnor when complete housed around 160 persons at any one time in single room accommodation, a hospital design concept that has only come full cycle again in the first years of the C21st.

Arthur Hill Hassall was well connected and moved rapidly to have his Hospital

designed, built and open. In June 1867 he published a prospectus. On this the

London medical journal The ‘Lancet’ commented on 22nd June 1867 in an

article titled ‘The Ventnor Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the

Chest’ –

“There are few spots, if any, in the British Isles, more highly favoured than is

the Undercliff, and indeed the whole Isle of Wight. The beauty and

picturesqueness of its scenery and fertility of its soil have led to its receiving

the appellation of ‘the Garden of England’: while the many advantages of the

situation, soil, and climate of Ventnor and the Undercliff have occasioned the

bestowal upon this particular portion of the island by a very distinguished

physician, Sir James Clark, of the title of ‘the British Madeira’. Indeed it is to

the writings of Sir James Clark that the Undercliff first owed its reputation, and

which, being well deserved, it has since maintained and increased.

“With so many advantages of scenery and climate, the latter specially adapted

to cases of phthisis, and in these days of seaside and convalescent hospitals,

it is singular that Ventnor should still be without an institution for the treatment

of the sick, in which they might participate with the more affluent and wealthy

visitors in the many benefits which is such a locality it would doubtless confer.

This want has presented itself to Dr. Hassall during his residence in Ventnor,

and as we learn from a preliminary prospectus which has been prepared, that

the gentleman is now engaged in the task of founding ‘THE VENTNOR

HOSPITAL FOR CONSUMPTION AND DISEASES OF THE CHEST.’ This

undertaking is not one of merely local, but even of national importance, since

the recipients of its benefits will come from all parts of the kingdom. The work,

therefore, of aiding in the establishment of such an institution is one in which

all classes and parties, not merely the Isle of Wight itself, but elsewhere

throughout the kingdom, may freely join. It is Dr. Hassall’s intention to place

the matter, as soon as the formation of the hospital shall have progressed to a

certain extent, in the hands of the Committee of Management. We trust that

Dr. Hassall will be well supported in his arduous and praiseworthy

endeavour.”

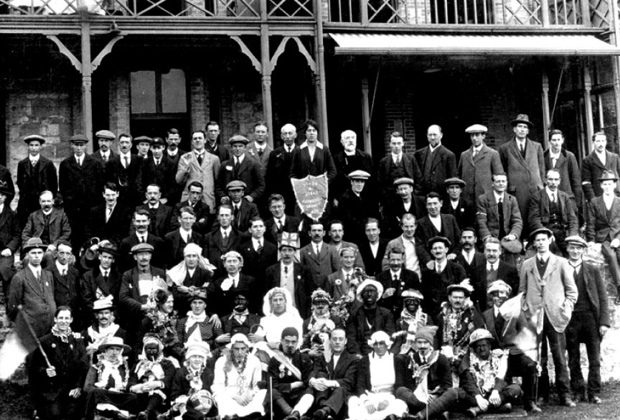

In February 1868 the first General Meeting of the new National Hospital for Chest Diseases was held at its Head Office in London, Piccadilly. Indeed it was from here it continued to be administered and managed until it was incorporated into the NHS an 1948. It had 370 founding donors, 80 of whom were from the Isle of Wight, amongst them members of the Brigstocke, Ingram, Mew, Oglander, Pelham and Tennyson families. The 1st President of the Governing Body was Viscount Eversley, former Speaker of the House of Commons and Governor of the Isle of Wight. Also holding office were Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, son of Queen Victoria, and Earl Roseberry, a former Prime Minister. The money to build the Hospital was raised entirely by private subscription and donation supported by a large number of fundraising events such as Balls, Grand Entertainment, Sermons and Church Collections, Fetes and Arts Festivals. A concert at the Albert Hall raised £228, a fete in Ventnor £46, and a Biennial Arts Festival at ‘Willis’s Entertainment Rooms’ St.James’, London £2,300. Individuals who donated £1000 or more had a bed named after them and included such persons as Samuel Courtauld, John Minton and Princess Louisa. John Jones of Piccadilly donated £70,000 in a legacy. The Hospital was built between 1868-1877, designed to Arthur Hill Hassall’s specifications by the architect Thomas Hellyer of Melville Street, Ryde. The builder was Ingram’s of Ventnor and stone was quarried at Gill Cliffs Road Ventnor. Land, of 26 acres eventually, was purchased in stages on the strip of the Undercliff on the side adjacent and facing the coast running out from Ventnor along the road between Lisle Combe and Steephill Castle and occupying the whole of the site that is now Ventnor Botanic Gardens. The Hospital opened to receive its first patients - male in November 1869 and female patients in March 1871. The Hospital was designed as a series of ‘Blocks’, initially 8, four for men and four for women, running east (F) – west (M), separated in between with a building housing the Chapel. Each ‘Block’ contained 2 ‘cottages’ side by side and interconnected by a central east-west corridor. Each cottage had 3 floors and a basement, The ground floor of each cottage comprised 2 sitting rooms each for 3-4 persons, separated by a corridor running north- south with the Entrance to the ‘Block’ opening onto the north side and Undercliff Drive. All the treatment areas of the ‘Blocks’ were south facing. The Sitting Rooms with French doors opened onto a veranda, and then directly on into the gardens. On both the 1st and 2nd floors of each cottage were 3 single person bedrooms – 6 in total for each cottage, opening onto south facing balconies. On these floors the corridor again ran east–west with bathrooms, wash rooms, kitchens, cupboards and nurses’ offices on the north side. All parts of the Hospital were strictly marked out as separate to men and women including the gardens. In the Basement was a subway running east – west connecting all 8 ‘Blocks’ with stone staircases to each block and store rooms under the sitting rooms. All the bedrooms were heated with hot water pipes from a central boiler gas and coal fired system. A well was bored and Reservoir made to hold 90,000 gallons. The construction cost for each ‘Block’ was in the region of £1,500.

The Chapel was built and opened in 1871-2 with daily services from a Chaplain although admission to the Hospital was not governed by religion. Stained glass windows were commissioned from the pre-Raphaelite artists William Morris, Sir Edward Burne Jones, Ford Maddox Brown and Sir William Reynolds Stephens. These are now relocated and on display in the nearby St. Lawrence Church following the Chapel’s demolition.

Between 1875 - 1877 a further new block known as the ‘Central Dining Hall’ was built to the west of the original 8 blocks – also known as the ‘Jones’ Block’ after its donor John Jones of Piccadilly and his legacy. Its foundation in 1875 was marked by a visit by the hospital’s neighbour at Steephill Castle the Empress of Austria. As there was a change in ground level on this part of the site this led to the ground floors of the new block being level with the basement of the original blocks. The new block again rose through 3 floors. The spacious Dining Hall on the south side rose through 2 floors from the ground floor to upper ground floor. Apart from the Chapel it was the one place where men and women, once well enough to leave their individual rooms and blocks could meet together although seating at dining tables remained separate. It housed an ‘Orchestration’ - a type of Organ, donated by Colonel Seely, which played military music and during later years the Hall became the centre for frequent Entertainments – plays and shows, devised and performed by patients and resident staff. To the rear were residential rooms for doctors and nurses. On the top floor were the kitchens, catering in all for 300 personspatients and staff, serving the Dining Hall below with dumb waiters. On the upper Ground floor north side was the Entrance Hall, Office and the Telephone, installed in 1887.

Two further blocks for patient bedrooms and treatment – taking the final total at the Hospital to eleven ‘blocks,’ were built in 1883 and 1897. The designer of these two was the architect T.R.Saunders and the builder A.Sims. In addition to the single veranda bedroom layout as previous they also contained facilities for occupational therapy activities with one room housing a full sized billiard table. In 1884 Queen Victoria visited and bestowed her patronage with the hospital becoming the “Royal” National Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest. In 1897 her daughter Princess Beatrice laid the foundation of block eleven.

In later years the spaces between each of the ‘Blocks’ were built in and enclosed to house new developments in radiology with X-Ray suites and Theatres for surgery.

The Gardens were extensively planted with walkways and paths for both exercise and leisure. Prince Albert sent over 6 palm trees from Osborne which were the first to be grown successfully in Britain. Sponsors included Veitch and Sons who donated bedding plants and 8 palms; Suttons and Sons who donated 1000 bulbs and ‘valuable plants’; Maurice Young who donated 1300 shrubs / trees, 200 fruit trees, magnolias and myrtles; W.H.Rogers who donated 800 shrubs and 60 fruit trees. The Hospital site also included a dairy farm, ranges for poultry and eggs, vegetable garden and orchard to enable the Hospital to manage and provide its own food supplies. 50 brace of pheasant came over each Christmas from Queen Victoria, and a miscellany of regular gifts including hogsheads of sherry, casks of port, 3 billiard tables, croquet sets, piano, table tennis tables, golf clubs, tobacco from Lambert and Butler and garments from the Isle of Wight Needlework Guild.

In 1877 Arthur Hill Hassall having completed the founding and building of the Hospital retired as its chief Physician and Medical Officer. He moved to live with his wife in Europe in the summer at Lucerne and eventually in San Remo on the Italian Riviera where he continued in private practice treating amongst others his close friend the poet and painter Edward Lear. In 1879 he published further work on the climatic treatments for tuberculosis with ‘San Remo and the Western Riviera Climatically and Medically Considered’. He wrote and published his autobiography ‘The narrative of a busy life’ in 1893. He died there in April 1894 leaving a will valued at £60 to his wife. A memorial service in his memory was held in the Central Hall at the Royal National Hospital at Ventnor on October 1894 at which a portrait commissioned from the artist Lance Calkin was installed. The painting can now been seen at St. Mary’s Hospital, Newport adjacent to Mottistone ward on the site of the former Hassall ward named in his memory.

Dr. Sinclair Coghill took over from Arthur Hill Hassall as Chief Physician in 1877 and held the post until his death in 1899. The first recorded matron was Miss Manger appointed in 1875. Dr. James Mann Williamson was appointed Resident Medical Officer in 1873 and his son Dr. James Bruce Williamson 1892 -1979 the Ventor GP also had a long association with the Hospital. He donated his father’s and grandfather’s collection of medical instruments to St. Mary’s Hospital IoW where they are now on display in the D’Olivera Library and Education Centre. The hospital also had a resident team of nurses from the outset, plus as was common in the C19th an extensive team of domestics, cooks, engineers, maintenance men, porters, waiters and farm workers. In 1924 a separate Nurses Home – Lampard Green House - was built on the site for 40 nurses, opened by Edward Prince of Wales. In 1948 a small house – Tanglewood – was purchased for night staff and the Matron. The hospital included a Pharmacy which dispensed an extensive repertoire of herbal and homeopathic prescriptions.

The Royal National Hospital for Chest Diseases at Ventnor, managed directly

from London, was a ‘Voluntary’ category Hospital. 75% of the population of

Britain at this time was working class with low income and scarce resources to

spend on their health. Arthur Hill Hassall’s Prospectus states:

“…the persons eligible must be necessitous and not in a position to defray

the entire cost of maintenance and medical treatment.”

“…each patient will be required to pay 10/- per week the sum must be paid in

advance.”

This was usually met either by the patient or their Sponsor/ Employer. The 10/- balance of the costs £1 per week for treatment were met by the private ‘subscriptions’ and donations to the Hospital Management London Office which continued to organise and promote their extensive range of fundraising events.

The mechanism for admission and acceptance as a patient was first by a person obtaining a ‘Letter of Recommendation’ from a Governor of the Hospital or by contacting the London office and its Secretary who would put them in touch with a Governor. This letter then had to be supported by a medical certificate from a medical referee or ‘Examining Physician’ in London – initially until 1875 Richard Hassall brother of Arthur Hill Hassall. The number of eligible ‘examining physicians’ was gradually expanded so by 1889 there were 5 and then expanding to every large town nominating a physician so by 1936 there were 536.

In 1871 Arthur Hill Hassall reported there were 99 patients treated who stayed

each for an average of 3months. Of these he reported 63 were much better

and recovering, 16 now well, 7 unchanged, 9 worse and 4 had died.

By 1879 the hospital was treating 580 persons in 102 beds

In 1889 630 persons in 132 beds

By 1900 780 persons of which there were always more men than women.

In 1904 817 persons were treated of who 761 were diagnosed with TB, 25 as

‘doubtful’ and 31 with other chest complaints such as bronchitis, asthma and

heart disease.

In 1880 the profile of male patients included:

Labourer, artisan, mechanic, servant, warehouseman, and clerk.

The female profile included:

Teacher, governess, housewife, servant, milliner, dress maker.

The cost of treatment at its opening in 1868 was £1.00 per week.

The arrangement whereby 50% of the cost was met by the patient (or their

employer/sponsor) payable usually at the outset of treatment and the balance

of 10/- by the monies raised by the Hospital Management Board from National

Subscribers and Donors continued largely until the hospital became part of

the NHS in 1948. If patients did experience difficulties in payment during their

treatment there was a discretionary fund established in the 1870’s, known as

the ‘Hamilton Fund’ to which they could look to for assistance.

The Fee remained at 10/- for 48 years.

In 1912 with the passing of the National Insurance Act the Patient Fee element could now be expected to be met by or contributed to by the local authority where the person lived.

The Fee increased in:-

1917 to 15/-,

1922 to £1.00

1932 to £2.00

1942 - £2.00

By 1932 the total weekly cost of a bed and treatment had risen to £3. 7/- 0d

per person per week.

By 1942 the weekly cost was £4. 9/- 0d.

A Fundraising Prospectus published in 1932 describes the RNVH as:-

‘Truly a “National Hospital’

“…And yet this very fact that it is a “National” Hospital is one of our greatest

difficulties in raising Funds, as it means that we have no great appeal to any

one locality, such as is the case with County Hospitals.

“Although 40% of our patients come from the Metropolitan Area, the King

Edward VII Hospital Fund (King’s Fund) cannot help us, as the Hospital is

situated outside the radius in which that Fund operates (viz., 11 miles from

St. Paul’s).

“Our subscribers have and are supporting us nobly, but the burden is heavy,

and if the charge to patients is not to be raised, new subscribers must be

found so that our work may not be crippled by lack of funds. Last year over

80% of the cases treated showed improvement. Will you help us to increase

this percentage?”

“Please send a donation however small!”

The 1932 Prospectus states that the total number of persons to have been treated since its opening in 1868 to have been 36,759. Of this total there is then a breakdown of the numbers from the 44 counties and ‘nations’ of the United Kingdom.

The largest is: London, including Middlesex @ 17,260

followed by: Hampshire 1,877

Surrey 1,734

Yorkshire 1,289

Kent 1,255

Sussex 1,111

Isle of Wight 969

Warwickshire 963

Essex 816

……..

Wales and Monmouth 474

Scotland 245

Ireland 155

……..

down to: Hereford 38

Cumberland 29

Rutland 19

Channel Islands 18

Westmoreland 12

Running Costs of the Hospital.

The annual cost in of running the Hospital of 160 beds was:

1878 £ 6,000

1880 8,383

1888 10,125

1917 17,806

1921 24,570

A break down of the annual operating costs in 1880 of £8,383 shows

expenditure of:

Provisions - £3,374, Medicines £273, Gas and water £269, Coal £292,

Combined Salaries of Medical Officer, Matron, Steward, Pharmacist £316,

Nurses and Servants £536, Office rent £167, Printing £108, Advertisements

£106, Head Office costs £312.

The annual breakdown of costs of provisions in 1880 was:

Meat – 36,404lbs @ £1,141 Poultry – 2,518lbs @ £160 Rabbits 318lbs @

£13 Fish – 2,574lbs @ £77 Bread – 33,908lbs @ £188 Flour 2,688 lbs @

£17 Milk – 55,048 pints @ £400 Butter 4,934lbs @ £255 Eggs 16,813 @

£101 Bacon 7,091 lbs @ £250 Tea, Cocoa, Sugar and Jams @ £312

Lemons 1,428 @ £9 Potatoes 1 ½ tons @ £9. 10/-

For staff: Beer 1,278 gallons @ £66 Bottled Ale 122 dozen £18.

Products in addition supplied by the Hospital Farm were:

Milk - 28,394 pints, Eggs - 8,334, Poultry - 504 lbs, Potatoes 10 tons and a

wide selection of vegetables and fruit.

Diet, nutrition and weight gain was always regarded as a key component of

the treatment and pathway to recovery. In the early years drinking of Milk

played a very important role. A typical daily menu was;

8.00am Milk - on awakening.

Breakfast – Coffee, Cocoa, bread and butter, sausage and fish.

Elevenses – Milk.

Dinner – Meat, roast or boiled, vegetables, salad and pudding.

Tea – Tea, Cocoa, bread and butter.

Supper – Porridge, bread and butter, Ale, Port, Wines and Spirits, Beef tea as

prescribed by the Medical Officer.

The Disease and Its Treatment

Phthisis – Consumption – Tuberculosis –TB are all names for the same infectious disease caused by strains of mycobacterium, discovered by Robert Koch in 1882 in Berlin and for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1905. TB typically attacks the lungs but can affect other parts of the body. It is spread, when persons, who have TB, cough, sneeze, or otherwise transmit respiratory fluids through the air. Classic symptoms are a chronic cough with blood tinged sputum / phlegm, fever, night sweats and weight loss. The disease was widespread on C19th Britain, especially in urban areas, and amongst persons exposed to harsh living conditions and outdoor exposure.

There was no cure for TB – until the discovery of the anti-biotic ‘streptomycin’ in the mid C20th and the safe application of the vaccine ‘Bacillus Camille – Guerin’ – BCG introduced in the UK in 1953. However there were a wide number of treatments developed and espoused by the medical profession and Arthur Hill Hassall certainly understood the infectious nature of the disease – hence his treatment on the ‘separate’ principle of single bedrooms for patients. Also through his microscopical examination of the bacteria contaminating the freshwater supplies of London’s drinking water he had an understanding of the possible origins of the disease.

Following his personal experience of the disease in 1866 and his subsequent recovery recuperating in Ventnor it was his firm view and the prevailing view of many others in the medical profession at the time was that climate, environment and the conditions under which the disease was treated were essential components to a possible recovery especially if applied in the early stages. The ‘temperate’ climate of Ventnor and the beneficial qualities of its unpolluted coastal air, combined with an environment offering complete rest and a healthy diet with regular nutritious meals to regain weight made him select the location and develop his style of treatment of the ‘sanatorium regime’. The importance of the climate to treatment is indicated by the fact that the job description of the Pharmacist included the responsibility to accurately record the daily meteorology of the site - regarding this as equally important if not more important than their skills and duties in making up medicinal prescriptions. In 1884 meteorological instruments to record the daily climate were installed in the gardens. Rainfall at the site had been recorded from 1873, temperature from 1880 and sunshine from 1881 by Dr. James Williamson the resident Medical Officer. It is recorded in the Board of Management meetings the Pharmacist being severely reprimanded for her failing to keep a fully detailed and accurate record and reason for considering her dismissal.

The location of the Undercliff selected also enabled him to ensure that the single sex, single occupancy bedrooms had access to south facing coastal fresh air via French doors and verandas, with heating as required in the rooms. This was where the newly admitted patient would stay for the first few weeks of their treatment and complete rest. When on the path to recovery meal times and social activity were redirected to the hospital’s central Dining Hall, Chapel and Gardens enabling visits and the journey time to be gradually built into the recovery schedule as strength and stamina were regained. For example on admission a new patient would be required to rest all day in bed in their room, allowed only to read, write, knit or sew.

From 12noon – 1.00pm and again from 5.00p – 6.00pm complete silence and no activity must be observed during 2 daily sessions known as the ‘Rest Hours’. After ½ hour their temperature would be taken and a chart compiled over 24 weeks. The system of body temperature records developed was unique to the hospital. During this progressive stage of the disease ‘absolute rest’ was required over several weeks with the only other activities allowed being talking and taking meals. For some persons with ‘tuberculous laryngitis’, a complication of pulmonary tuberculosis, no talking was allowed either.

When the person’s temperature remained normal over a week and weight was constant or no longer falling the person could progress to sit in a deck chair for 2 hours daily on the veranda and to recover their colour. When they were well enough to be out of bed for 4 hours they could visit the Dining Hall for the midday meal – with the return walk of 200yards part of the recovery plan. The next 3 stages were ‘Up all day’ from 8.00am – 9.00pm; then ‘Daily walks’ the first being of 2 daily walks of 5 minutes to chairs in the garden where they then rested. The 2nd stage was 2 daily walks of 10 minutes then 15 minutes leading to ‘outside hospital ‘walks of 30 minutes along St. Lawrence road and around the garden footpaths – men in the morning, women in the afternoon. Gradually the 2 x 30 minute walks were extended until the person was well enough for discharge after maintaining this schedule for 6 weeks.

For a period commencing in 1907 up to 1914 a routine of physical ‘work’ for patients was introduced in the gardens. The aim was through graduated exercise to stimulate a slight recurrence of the disease to build up an immunity. For men it was graded into five stages commencing with the carrying of loads of 12lbs such as carrying vegetables to the kitchen. The final stage included breaking the ground with picks and moving stones and earth in wheelbarrows. For women the first stage was carrying loads up to 9lbs and the heaviest involved digging and rolling lawns. They were also expected to carry out housekeeping duties such as dusting, bed making and preparation of vegetables.

This efficacious combination of climate, structured environment and strict ‘sanatorium’ regime, was supported by medicinal and pharmaceutical prescriptions derived from plants and minerals tested by trial and error over many previous generations in a complex list of bio-chemical interactions. These treatments lasted well into the C20th and are still today often the essential basis for many contemporary over the counter products in high street chemists.

We are able to establish what treatments persons received at the Royal National Hospital as patient records were kept for each patient until the early C20th, and these are now kept in the Isle of Wight County Archives, and the individual treatments were decoded by consulting with the ‘British Pharmaceutical Codex - BPC’ of 1907.

C19th doctors prescribed a series of treatments in the form of:-

- Tonic. A ‘lift’ of botanical or chemical source dissolved in water.

- Tincture. Substances again to ‘boost’ dissolved in alcohol + spirit.

- Mixture. Either the above combined or other additions added to water to produce a ‘curative’ or ‘alleviate’ product e.g. cough mixture or bottle of medicine apportioned. Syrup usually added for taste.

- Liniment. Substances combined and rubbed onto/ through the skin. Can be applied as a patch or a ‘plaster’ or ‘paper’.

- Lozenge. Substances of bio-chemical source combined with sugar paste.

- Pill. Substances of bio-chemical source combined and apportioned.

- Drinks. Alcoholic beverages such as ‘orange wine’ or ‘sherry’, Cod Liver Oil, and Milk were all favoured.

Treatments and medicines prescribed in the Patient’s Notes:-.

- Pil (ule) Conii. This was a favoured prescription and a widely used homeopathic remedy prescribed on the principle that ‘like cures like’ in a very small dosage. It is made from an extract of Conium leaves Conium maculatum more commonly known as Hemlock, a widespread Mediterranean plant. It is highly poisonous and in larger quantities causes paralysis leading to death (death of Socrates). Its purpose was as a mild sedative anti spasmodic.

- Combined in the prescription is also possibly Ipecacuanha Cephaelis ipecacuanha. The plant is found in Brazil and the dried rhizome - root is used. It is used as an expectorant to clear the chest and respiratory tract. Syrup of Ipecac has been used as a cough medicine well into the C20th. The substances were combined as a Tincture and treacle added to taste.

- Pil (ulae) Colocynthidis. Composed of extract of Colocynth from the bitter cucumber/ desert gourd found in the Mediterranean basin. Used as a purgative. Combine 1.1 gram colocynth, 13 grams aloes, resin of scammony – convulvulous / bindweed from the Mediterranean 13 grams, oil of cloves. Used as a laxative.

- Pil Rhei Co. Pilulae Rhei Composita was a common Tonic used as a laxative. It consists of Rhubarb powder – 13 grams, Socotrine of Aloes (from Indian Ocean/East Africa) -10 grams, Myrrh in fine powder – 6 grams, Soap in powder -14 grams and 2 millilitres Oil of Peppermint and water sufficient to make 100 pills kept in a loosely stoppered jar to prevent going mouldy.

- Pil Atropin. Used for nightsweats. Atropine was combined with morphine, sugar and glucose. Atropine is now listed by the WHO as one of the world’s essential medicines. It occurs naturally in Deadly Nightshade, Jimson Weed, & Mandrake.

- Chlorodyn (e). A famous patent medicine in the UK invented in the C19th by Dr. John Collis Browne a doctor in the British Indian Army. Original treatment for cholera also to relieve pain and as sedative. Ingredients a mixture of laudanum – alcoholic solution of opium – tincture of cannabis and chloroform.

- Decoctum Cetraria. Lichen – Icelandic Moss. Growing abundantly in northern Europe. Used traditionally to relieve chest ailments. As a decoction or mixture with the lichen macerated in distilled water, boiled and strained 12ozs combined with potassium nitrate –saltpetre 1 ½ dram (diuretic), dilute nitric acid ½ oz, dilute hydrocyanic acid 20 grains and Oxymel – honey 9 drams

- Quinine Disulphate – as a Tincture. Quinine is a white crystalline alkaloid having antipyretic – fever reducing, analgesic – pain killing, and anti inflammatory properties with a bitter taste derived from the bark of the cinchona tree in Peru and Bolivia. 24 grains of Quinine powder were dissolved in1/8 oz or 1 dram of dilute sulphuric acid and added to a tincture of ginger – 2 drams and taken as a tablespoonful in water twice a day. Quinine was used for the treatment of the symptoms of malaria in India and is still used in and the product marketed as the common ‘Indian Tonic Water’ with gin etc.

- Morphine and Ipecacuanha Lozenge. Morphine is an opiod analgesic acting on the central nervous system to reduce pain derived from the dried latex of unripe seedpods of the opium poppy.

- Tincture of Scillae. Made from Squill a perennial plant with a large ovate bulb native throughout the Mediterranean. It is used most likely at RNH as diuretic and expectorant.

- Tincture of Gentian. Derived from the dried rhizome common Central European blue flowering plant it is commonly used in herbal remedies to treat digestive problems and stimulate appetite. Prescribed as a tonic it combines 2 drams of dilute Hydrochloric Acid with 2 drams of Spirits of Chloroform and 4 drams Tincture of Gentian with 6ozs of water as a syrup.

- Ammonium Chloride. - sal ammoniac. Used as an expectorant in cough medicine

- Ammonium Acetate and Potassium Nitrate Mixture. Ammonium Acetate is a chemical compound derived from the reaction of ammonia with acetic acid. Potassium Nitrate is a salt commonly known as Saltpetre. Commonly used since the Middle Ages as a food preservative and now in gunpowder and fertilizers. At the RNH there use was mostly as an expectorant. 6 drams of AA were combined with 30 grams of PN.

- Hydrocyanic Acid. Hydrogen cyanide, also known as Prussic Acid, is highly poisonous and commonly used in pharmaceuticals. It is found in many trees and shrubs of the order Rosaceae - Wild Cherry and Almond. When dissolved in water it produces hydrocyanic acid. In this case 12 minims – drops were combined with 6ozs of water + syrup and 1 tablespoonful taken every 4 hours. In this dilute form it was probably used as a sedative to reduce spasm and coughing.

- (Vinegar of) Cantharides. Acetum cantharidis. Made from the dried beetle Cantharides common in southern Europe amongst olive trees, from which the substance cantharidin is derived. It was a constituent in a ‘warming plaster’ or liniment and applied and rubbed into to the skin. Often also mixed with mustard and soap to create the liniment. Vinegar of Cantharides was presumably used to encourage decongestion in this case on the chest or throat. If used in stronger forms can cause blistering of the skin which in certain cases was encouraged. A contemporary use is to stimulate growth of hair.

- Spirit of Camphor. Spititus Camphorae. Both a stimulant and antispasmodic prepared as a tincture. Derived from the wood of the Camphor Laurel, an evergreen tree in Asia – Indonesia. It has a strong odour – mothballs, and when rubbed on the skin produces either a cooling or warming sensation. It is an active ingredient in ‘Vicks Vapo rub’.

- Tincture of Ginger. Made from the ginger root it is used as an aromatic carminative as a purgative and to reduce flatulence.

- Tincture of Cinchona. The dried bark of the cinchona tree – source of quinine, dissolved in phosphoric acid. Used sparingly it improves digestion and tones muscular and nervous systems in diseases and exhaustive illnesses and alleviates night sweats.

- Spirits of Chloroform. Prepared by the chlorination of ethyl alcohol or methane and found naturally in seaweed it was widely used as an anaesthetic in the C19th and at childbirth – by Queen Victoria. Large doses are toxic. It was probably used as a sedative at the RNH Ventnor.

- Tincture of Hyoscyamus. Hyoscyamus niger. Made from the leaves of the common plant Henbane. A cerebral and spinal sedative used for insomnia and to prevent gripe.

- Tincture of Chloride of Iron – Ferri perchloride. Atomised as spray for chronic immflamation of air passages. Iron dissolved in acid – hydrochloric / sulphuric / muriatic and then added to alcohol. Tannic Acid. Probably derived from oak bark or leaves. In this case combined with glycerine and used as a gargle for the treatment of sore throats.

- Iron and Quinine Tonic. Used as a ‘restorative’ to increase appetite, encourage sleep and build up mental, nervous and muscular energy.

- Quinine and Magnesium Sulphate. Magnesium Sulphate is a naturally occurring inorganic salt – commonly known as Epsom Salts. Used as a bronchial decongestant.

- Chloral Hydrate. Easily synthesised through the chlorination of ethanol. Used widely as a sedative in the C19th.

- Potassium Bromide. Made by the reaction of potassium carbonate with the bromide of iron in turn made by treating scrap iron under water with bromide. Used widely in C19th as anticonvulsant and sedative.

- Gold Cyanide. Injections of gold salts began at the end of the C19th for their apparent effectiveness against the ‘mycobacterium tuberculosis’. Very toxic in large doses.

- Ferri Perchloride. Taken internally as an astringent or as a throat spray. Used externally as a styptic (stops bleeding).

- Liniment ‘Terebinth Canadensis’, Canada Balsam or more commonly known as Turpentine. Made from the resin of the balsam tree. Used as a chest rub to ease congestion.

- Liniment of Iodine. A naturally occurring chemical element e.g. in seawater. Used as an antiseptic and also probably as a decongestant.

- Liniment of Croton Oil. Prepared from the seeds of the tree ‘Croton Tiglium’ found in India and Malay Archipelago and Malabar. Used as an exfoliating emetic externally causing burning sensation. Caustic and dangerous.

- Liniment of Mustard Leaf. From the mustard plant – now widely used as a nutritious vegetable.

- Lin Sapor. Soap based liniment combining pieces of soap, camphor, oil of rosemary, water and alcohol. Usually applied between the shoulders.

- Charta Epispasticia. Mustard paper as liniment.

- Essence of Senna. Made from the Senna plant and used as a laxative.

- Beef Tea. A meat extract – ‘Bovril’, consumed as a drink. C19th ‘restorative’.

- Oil of Morrhue - Cod Liver Oil. A nutritional supplement derived from the liver of cod fish high in omega3 fatty acids, vitamins A and D.

- Oil of Ricini – Castor Oil. Made from the seeds of the castor oil plant, a native of India. A mild purgative used for constipation

- Confection of Rose. Rose Hip syrup. High in Vitamin C.

- Milk. Unpasteurised. Considered essential for building weight, strength and energy

The following is a summary of the Patient Notes for the first patients treated at the Royal National Hospital for Chest Diseases – male and female. Hand written notes were kept giving a brief description of the patient’s daily condition, the progression (recovery) of the illness, their weight and temperature, and the prescriptions and medication instructions to the pharmacist and nursing team.

Whilst the entries were scrupulously maintained for all persons receiving treatment throughout the C19th the handwritten and medical shorthand can on occasion make them difficult to decipher.

All records commence with a ‘Medical Certificate’ authorising treatment from the London Piccadilly Office, giving registered personal details of the patient, a short medical history, diagnosis and prognosis, and medical examination and report.

The first person to be treated at the Royal Hospital for Chest Diseases at

Ventnor was:

George Keith, Clerk, Age 21.

Recommended by Governor Joseph Diggle. Approved by Douglas Powell MD

Diagnosis Phthisis/TB 2nd stage: Prognosis: Improvement – unlikely to be

permanent.

Medical history – Previously treated at Montreal Military Hospital. Broken

blood vessel with much bleeding caused by exposure. Expectoration (phlegm

discharge from the throat) in the morning, hard cough, sleeps well, pain when

lying, appetite good, bowels irregular sometimes loose, night sweats, strong

enough to walk (several miles if required). Pulse 104.

Admitted 4th November 1869.

06.11.1869. Treatment Prescribed: Liniment of ‘Terebinth Canadensis’ – Oil of

Turpentine. 3ozs applied night & morning. Pil Conii, 5 grams Night & morning.

Tonic not advised at present however Cod liver Oil in a few days.

08.11. Prescribed; Cod Liver Oil – desert spoonful twice a day twice a day.

Tonic of 24 grains of Quinine (powder) dissolved in 1/8 oz or 1 dram of dilute

Sulphuric acid added to a tincture of Ginger – 2 drams. A table spoonful in

water twice a day.

11.11. Repeat treatment.

15.11. Cough not so harsh, throat sore. Liniment applied ‘so as to nearly

blister’. Continue treatment. Weight: 8stone 10lbs.

18.11 Feels better. Liniment of Iodine to be applied with camel hair brush

occasionally. Continue treatment.

22.11. Feels weaker but cough better. Treatment continues: Pil Conii. 5 grams

one at night & morning. Beef Tea at 11.00am.

25.11. Sleeps better, Cough still troublesome. Pulse 126.

Treatment: Apply Liniment to throat for a short time.

28.11 Treatment: Mustard application to chest.

Morphine and Ipecacuanha Lozenge – Occasionally.

29.11 Pulse 104. Weight 8stone 9 ¾ lbs

Treatment: Tonic. 2 drams of dilute Hydrochloric Acid +

2 drams Spirits of Chloroform + 4 drams Tincture of Gentian + 6 ozs of water

– as syrup. A table spoonful three times a day. Continue Pill.

02.12. Breathing hurried. Expectoration increased. Pulse 120.

Treatment: Milk at 8.00. Mixture – Ammonium Acetate 6 drams, Potassium

Nitrate 30 grams, Tincture of Conii 2 drams, Hydrocyanic Acid 12 minims

(drops), Water 6ozs, Syrup. A tablespoonful every four hours.

+ Morphine Hydrochloric 1 grain with Conii Extract 15 grains – mixed –

divided into 4 pills. 1 at night. Omit Cod Liver oil for a few days.

06.12. Respiration less frequent. Pulse 100. Continue treatment. Repeat

Mixture and Tincture.

9.12. Much the same. Good appetite. Continue treatment.

13.12. Weight 8 stone 12 lbs.

14.12. Pulse 126. Continue treatment.

17.12. Expectoration small in quantity. Pulse very frequent. Has many fits of

shivering. Cold in feet and legs. Cough hard and causing retching.

Treatment: Pil Rhei Co. 5 grams. Two at night. Continue Cough pills.

Lin Sapor Liniment .Vinegar of Cantharides - Acetum Cantharidis 2 drams.

20.12. Expectoration tinged with blood. Breathing less hurried. Pulse same.

Treatment: Increase strength of liniment. Cod Liver Oil - a desert spoonful

twice a day. Orange wine. Pil Rhei Co. if required.

23.12. Is better. Expectoration not discoloured. Less shivering but pain in

shoulder. Treatment: Mustard liniment to chest. Lin Sapor 2ozs. Vinegar of

Cantharides 4 ozs. Orange Wine at 11.00 instead of Sherry.

28.12. Not so well. Pain in side very acute. Hysterical. Breathing

spasmodically affected on left side. Weight 8 stone 8lbs.

Treatment: Tonic of Iron and Quinine 2 drams + Sprit of Chloroform 1 ½

drams + Spirit of Camphor 1 ½ drams. A tea spoonful twice a day after meals

30.12. Treatment: Resume Cod Liver Oil. Pil Conii. Continue Mixture.

Morphine. Milk.

02.01.1870. Is better. Continue Treatment: Pil Conii – 2 at Night.

03.01. Is better. Continue treatment.

06.01. Is better. Expectoration small and ‘not rusty’.

10.01. Is much better. Respiration easier. Expectorant very small. Pulse 106.

Treatment: Apply Liniment to throat. Omit Cod Liver oil for a few days.

Continue with treatment. Weight 8 stone 9 ¾ lbs. Gained 1 ¾ lbs.

17.01. Is not quite so well. Pulse frequent. Expectorant very small.

Treatment: Repeat Mixture. Add Tincture of Ginger.

Apply Mustard Liniment to chest at night and continue.

20.01. Is not quite so well. Throat troublesome. Treatment: Mixture - Spirits of

Chloroform 2 drams, Tincture of Hyoscyamus 3 drams, Spirits of Camphor 1

dram, Water 4 ozs, Syrup. A table spoonful every 4 hours.

+ Tannic Acid – 20 grains with Glycerine 3 drams + Water 10ozs as Gargle.

24.01. Weight 8 stone 5 ½ lbs. Lost 4 ¼ lbs.

25.01. Is rather better. Throat Better. Appetite good. Pulse 120.

Treatment: Iron and Quinine Tonic. Tincture of Ginger. Gargle. + Liniment.

+Pil Conii. +Lozenge.

27.01 1870. ‘Returned Home of his own accord. Considerably benefitted’.

Comment: As the first patient George Keith seems to have been offered the full ‘vocabulary’ of medicines and treatments considered appropriate for treatment of consumption in the second half of the C19th century – Pills, Tonics. Mixtures, Liniments, Lozenges, Gargle, Restorative beverages all offered to alleviate symptoms rather than having any great curative function or role. Medicine was a partner in the treatment along with complete rest in a single sex room, access through French doors onto a balcony and later into the gardens (again single sex) and a sanatorium regime of fresh air, enjoyment of the temperate climate and gentle exercise.The location of the hospital at Ventnor on the undeveloped southern English coast with its unique climate and environment were considered the main restorative instruments and factors leading to recovery more than medicines. Regular monitoring of weight, pulse and temperature are also a feature to determine progression. The length of stay of 3 months is the normal period contracted for financially at the outset of treatment. The discharge report ‘Retuned home of his own accord – Considerably benefited’ is the standard reported outcome for most cases.

Louis Etienne Lafor. Age 20.

Recommended by Mrs Ingram. Wrexham.

Diagnosis: Consumption both Lungs for 7 months. Cavity right lung. 3rd stage.

Prognosis: Rather unfavourable. Benefit hardly likely to be permanent.

Medical Officer. Thomas Taylor Griffiths F.R.C.S. Originally declined

admission but decision reversed. 12.10.1869.

Weight 10 stone.

Pulse variable 100 – 118.

04.11.1869. Admitted.

06.11. Treatment: Extract of Conii 4 grains. Morphine Hydrate ¼ grain

6 pills – one each night.

+ Mixture - Spirits of Ammonium 3 drams, Tincture of Scillae 2 drams,

Tincture of Conii 3 drams, and Camphor 6 ozs. + Syrup. A table spoonful in

water when the cough is troublesome. 6ozs = 12 doses.

08.11. Treatment: Quinine Disulphate 1 dram. Make into 10 pills. One three

times a day.

+ Confection of Rose (Rose Hip Syrup).

+ Beef Tea twice a day.

+ Oil Jec Assel 3 drams (unknown medication)

+ Fire in Room if required.

11.11. Treatment: Liniment Terebinthine Aceticum 2 ozs at night.

+ Mixture - Potassium Nitrate - Saltpetre 1 ½ dram, Dilute Nitric Acid ½ oz

Oxymel – Honey 9 drams, Dilute Hydrocyanic Acid 20 grains, Decoctum

Cetraria - Lichen12 drams. A tablespoonful four times a day.

13.11. Treatment: Charta Epispastica - Mustard paper applied between the

shoulders.

14.11. Treatment: Bottle of medicine 6 ozs - Tincture of Scilae 1 dram, Spirits

of Ether Sulphate 1 ½ dram, Spirits of Ammonium Acetate 1 ½ dram, Syrup 2

drams, Water 6 ozs. To be given when the breath is troublesome.

+ Emplastrum Vericalis (unknown medication).

18.11. Treatment: Omit Potassium Nitrate from mixture. Repeat Mixture

and dosage

22.11. Treatment: Tonic - Iron and quinine Citrate 12 grains

Syrup 1 dram and water 6ozs. A desert spoonful occasionally.

25.11. Continue treatment.

28.11. Died at 2.45 am.

Comment. Louis Etienne Lafor was the second patient to be admitted and the

treatment was not successful. Persons diagnosed at 3rd stage Phthisis /

Consumption were subsequently rarely admitted confining admission to 1st

and 2nd stage only as presumably it was determined that neither the

medicines or recuperative environment would be able to respond sufficiently

to making a successful discharge and outcome.

During the life of the Hospital fatalities did continue to occur and a plot of land

was purchased on the north side of Undercliff Drive as a resting place/

graveyard.

Archibald Charles Adkyn. Age 26.

40 Manchester Street, Manchester Square. London W.

Recommended by His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch.

Medical Officer: Mitchell Bruce MD, 60 Queen Anne Street, London W.

18th October 1879.

and Medical Officer: Dr. Cockle FRCP, 12 Pall Mall, London at 12.40pm on

Thursday October 23rd 1879

Diagnosis: Phthisis, 3rd stage

Prognosis: Favourable comparatively.

Medical History: Has had ague in India. About the middle of last year began to

suffer from indigestion and had malaria fever in India. In august of last year

began to cough and expectorant light and also had profuse night sweats. In

December he had haemorrhage and grew worse until the end of February

when he had haemorrhage for several days. The night sweats left him but in

August this year he became worse and had haemorrhage for about a week.

Since June of this year frequently vomits food. He has lost about a stone in

weight this year. Present state – cough worse especially after breakfast and

tea. Expectorant very frothy. Had slight night sweat yesterday. Since Saturday

last has had occasional sharp pain in right lumbar region but feels better

today. Appetite fair. Tongue furred and indented. Frequently vomits after food.

Bowels rather irregular

13.11.79. Evening Temperature 102.4. Pulse 97.6. Slept well Slight sweating.

Feels cold and shivering today. Cough very bad. Expectorant after meals.

Treatment/ Prescription: Tincture Acid Hydrochloric

14.11. Slept fairly. Sweating. Cough easier. Treatment: Pil Atrop.

16.11. Urine – normal. Felt sick and faint. Pulse 92, weak. Constipated.

Treatment Pil Rhei Co. 8 grams.

17.11. Bowels still confined. Slept badly. Still feels sick.

Treatment: Oil of Ricini.

18.11. Bowels have acted freely. Feels better today.

19.11. Sweating again always at 2.30am Treatment: Pil Atrop.

20.11. In bed. Cough still troublesome. Treatment Chlorodyn.

22.11. Sick am. Bile. Treatment: Sodium Sulphate and Ammonium Chloride.

26.11. Much better. No sweating. Cough diminished and appetite improved.

02.12. Much better. Spit rather more today. No sweating. Bowels regular.

03.12. In bed.

09.12. Much better. Cough still troublesome. Spit considerable. Sweating last

night. Treatment: Inhale Cat Cr (?)

14.12. Urine 100ozs. Specific Gravity 1023. No sugar.

16.12. Very much n better. Tongue clean. Appetite good. The spleen causes

much pain on walking. Has to get up several times in the night to make water.

Urine 80ozs. Treatment: Codeine, Quinine Sulphate. Tincture Gentian.

17.12. Weight 9 stone. Urine 101 ozs. / 11.00am – 8.00pm 8ozs. 8.00pm -

10.00pm 48ozs. 10.00pm -11.00am 45ozs.

18.12. Urine 75ozs.

19.12. Urine 90ozs.

22.12. Urine 95ozs. A little colour in spit.

30.12. Not so well. Urine still excessive. 75ozs. Feverish today.

31.12. Weight 8 stone 13 ¼ ozs.

02.01.1880. Much sweating. Treatment: Stop Pil Atropin. Start Pil Ricini.

Urine specific gravity 1010. Watery appearance. No alb. No sugar.

06.01. Troubles with the water again. Less sweating. Appetite fair.

08.01. Spit still bloody. No sweating.

13.01. Sick this morning. Costive. No sweating. Making less water.

14.01. Not so well. Sick again today. Weight 8 stone 12 ¼ ozs.

20.01. Spit less. Cough rather troublesome. Still gets up at night to make

water. No sweating. Still rather costive.

23.01. vomited bile this morning. Motions still hard. Urine faintly acid, high

coloured, normal.

27.01. Chest feels ‘stuffy’ at night. Spit 4ozs, frothy. Bowels regular. No

sickness. Tongue furred. Sweating last 2 nights.

Weight 8stone 10lbs.

29.01. Still sweating as before.

30.01. A little sweating last night.

31.01. Almost no sweat last night.

03.02. Much sweating since last report. Flushing and fullness after dinner.

Pains in back and chest.

Treatment: Warburg’s tincture every 4 hours.

08.02. Ague attack. Commencing at 10.00am. Temperature at 12.00 = 102°

Temp at 3.00pm = 101.8°, at 7.00pm = 99.8°.

09.02. Not well today, was very hot during the night. Pulse 124. Headache

and chilliness. Temperature at 3.00pm = 100.8°. The Warburg’s causes

gripes.

Treatment: Quinine Sulphate 10grains.

10.02. Temperature 12 noon = 103°. To have hot tea ad lib at commencement

of cold fit.

11.02. In bed.

12.02. Quinine Sulphate 10 grains at 11.00am. Pil Atropin.

13.02. Quinine Sulphate 10 grains every 2 hours.

14.02. Treatment?

16.02. Ammonium Chloride 25 grams 4 times daily.

24.02. Quinine at 6.00am and 9.00am

25.02. In bed.

06.03. Weight 8stone 5 ½ lbs

08.03. Pain and friction near left nipple.

10.03. Very large moist? in left upper 3rd, advancing

Weight 8stone 7lbs

End of record. 10.03.1879

Comment. Charles Archibald Adkyn was a 3rd stage patient admitted 10 years after the founding of the Hospital. His stay of nearly 5 months is an indication of the difficulty of treating the illness and the slowness of his ability to respond. Indeed his discharge is accompanied with an uncertain prognosis. Continuous monitoring and recording of his vital signs appears to be a significant aspect of his care and treatment.

The first female patient was:

Ann Whitchurch. Age 48. 50 High Street, West Cowes.

Recommended by Lady Cheape,

Admitted by Edward Gibson, Bath Road, West Cowes.

Diagnosis: Chronic Bronchitis. Incipient Phthisis. Suffering from bronchitis for

15 years, pneumonia 12 months ago, laid up for 5 months, sweats at night but

not currently, suffers from dyspepsia and constipation of bowels.

Prognosis; Favourable however doubtful permanent benefit.

Admitted March 23rd 1871.

Height: 5 ft.2½ ins. Weight: 8st.7½ lbs. Temperature 95.5°F. Pulse 78. Chest

measurement 30. Cough and Expectoration.

23.03.71. Sleeping very well.

Treatment: Infusion Gentian Tonic. Ammonium Carbonate. 3 times a day.

Oil of Morrhue. 3 times a day.

31.03. Bowels have not opened for 3 days.

Treatment: Pil Rhei Compound 4 grains

03.04. Bowels still very confined.

Treatment: Oil of Ricini 3 teaspoons.

06.04. Improving but complains of some tightening of the chest.

Treatment: Desci Canii 20ozs - unidentified prescription.

Spirit of Chloroform 10ozs to 3 teaspoons of water.

Extract of Hyoscyamus 10 grains

Extract Calae compound 10 grains – possibly a sedative.

Pulse 72.

10.04. Weight 8st.8½ ozs.

13.04. Cough improved.

15.04. Treatment: Liniment of Iodine to breast.

20.04. Expectoration less.

Treatment: Mixture Quinine and Magnesium Sulphate.

24.04. Weight 8st.9¼ ozs.

01.05. Cough improved, no expectorant.

Treatment: Potassium Nitrate, Potassium Sulphate, Hydrocyanic Acid,

Tincture of Gentian. 3 times a day. Liniment to be applied to ankle.

12.05. Has a collection of matter at the corner of the left eye.

Treatment: poultice.

20.05. Eye better. Pain in chest. Cough improved.

Treatment: Pil Rhei. + Tincture of Cinchona ½ dram. + Phosphoric Acid

10 ozs three times a day.

23.05. Weight 8 st.11¾ ozs

Treatment ceased.

Comment. Female patients were not admitted until two years after the first male patients and at first there were a significant larger number of men over women admitted for treatment. However persons were referred from all over the country, including local Isle of Wight residents, as befits the title of the ‘National Hospital for Chest Diseases’. Many persons lodged in Ventnor prior to admission but staying on after discharge was actively discouraged.

Mary Ann Crompton. Servant. Age 27. 49 Castle Street, Reading.

10.03.71. Recommended by Lady Crewe.

Diagnosis: infection of throat and bronchitis. Treated at Berkshire Hospital for

1 month. Expectorating a small quantity of blood.

Admitted 23.03. Height 5ft 3½ ins. Weight 7st.12 ozs. Pulse 76.

Temperature 98.2°. Chest measurement 31. Cough slight. Expectorant normal.

Treatment: Tincture of Cinchona 3 grams. Magnesium Sulphate 20 grains,

Ferri perchloride 20 minims with 2 ozs water.

Oil of Morrhue 3 teaspoons twice a day.

31.03. Complains of pain in her side.

06.04. Improving.

11.04. Weight 8st.¼ oz.

13.04. Cough easier. Expectorant very slight. Appetite good. Bowels

constipated.

Treatment Rhei compound. 10 grains at night.

Turpentine liniment.

16.04. Bowels very constipated.

Treatment: Magnesium Sulphate 20 grains.

Essence of Senna Compound concentrate – 1 teaspoon.

Infusion of Rhei Compound – 1 dram+ water 1oz.

Every 3 hours until bowels are relieved.

20.04. No expectorant. Very little cough.

28.04. Weight 8 stone.

06.05. Improving but headaches.

08.05. Improving.

20.05. Is better. Cough less and no expectoration.

Weight 7stone 12 ozs.

03.06. Improving.

05.06. Treatment: Tincture of Cinchona, magnesium Sulphate and Iron.

10.06.Continue treatment.

17.06. Continue treatment.

Weight 7st. 12½ ozs.

24.06. Improving – continue treatment.

30.06. Continue treatment.

Weight 7st 12¾ ozs.

08.07. Continue treatment.

17.07. Continue treatment. Rather bilious today.

Weight 7st 10½ ozs.

24.07. Continue treatment.

04.08. Weight 7st. 10½ ozs.

08.08. Continue treatment.

09.09. Almost well.

Comment. Mary Ann Crompton stayed 6 months, an unusually long time and received little recorded treatment by way of medicines. It was in fact a common practice for employers of servants, in this case Lady Crewe, to pay for persons they did not want to return any time soon and presumably she paid for this privilege and the Hospital which had to charge for 50% of its costs reciprocated.

Mary Brown. Age 19. Dressmaker. 10 Ashby Place, Osborne Road,

Southsea.

Admitted August 17th 1871.

Chest measure 29 ½. Pulse 88. Respiration 24. Height 5ft ¾ in.

Weight 7 stone.

Diagnosis: 1st stage consumption.

19.08.1871. Expectorant 6 drams.

Treatment: Mixture of Morphine and Chloroform each night.

Tonic – Iron Citrate and Quinine 4grains 2times a day.

28.08. Pain after meals.

Treatment: Bismuth and Hydrocyanic acid – for indigestion.

07.09. Cough and expectorant diminished.

Treatment: Bismuth Carbonate.

15.09. Treatment: ‘Emplastrum Syttae ‘– a form of liniment.

21.09. Cough better. Expectorant small. Continue Bismuth treatment.

Experiencing sleeplessness. Treatment: Chloral Hydrate as sedative.

Bread and milk in the evening.

22.09. Complains continually of no sleep. Previous medicine Chloral Hydrate

and morphine. Treatment Opium pill at night ½ grain.

Weight; 7stone 6 ½ lbs.

29.09. Omit Bismuth.

Continue Quinine Tonic.

05.10. Much better.

12.10. Weight: 7stone 10 ¾ lbs.

16.10. Mustard Leaf liniment.

19.10. No expectorant, slight cough.

Treatment: Iodine liniment.

23.10. Pain in right side.

Treatment: Liniment of Croton Oil.

24.10. Weight 7stone 13 ½ lbs.

26.10. Continue Mustard leaf liniment.

02.11. Continue Mustard Leaf liniment.

09.11. ?

15.11. Weight 8stone 1 ¼ lbs.

18.11. Left Hospital ‘considerably improved’.

In 1890 Dr Coghill, Dr. Arthur Hill Hassall’s successor, visited Robert Koch in Berlin to learn more about the supply of the ‘lymph’ or ‘Koch’s Old Tuberculin’ as it was more commonly known, a sterile liquid containing the growth products extracted from the tubercle bacillus, although it proved to be ineffective as a form of treatment. In 1889 two rooms at the hospital were allocated for scientific research and in1899 a Pathology Laboratory was established to identify the ‘Tubercle bacilli’.